Can Public Transport Improve Accessibility for the Poor Over the Long Term? Empirical Evidence in Paris, 1968-2010

Abstract

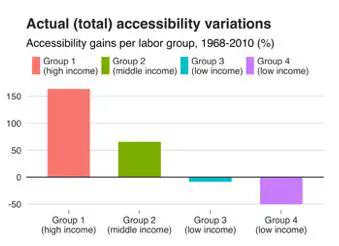

It is difficult to cut transport greenhouse gas emissions without affecting negatively the poorest people. A solution, in cities, is to target low income districts with public transport investments. However, after a few years, changes in neighborhoods, especially transit-induced gentrification, may prevent the social objective to be met. Whether public transport actually leads to population displacement has been extensively studied empirically, but the literature is inconclusive: the longer-term impact of such investments remains unclear. Here, we study the evolution of job accessibility in Paris metropolitan area between 1968 and 2010, by income and labor group, following the changes in the transport network. We show that major public transport lines, when they were built, served the needs of all groups in an almost neutral way. However, a few years later, due to population and job movements, actual changes in accessibility systematically resulted in gains for richer households and losses for poorer ones. Such a pattern is consistently observed in every decade between 1968 and 2010. It appears to be due primarily to unequal changes in the numbers of jobs in each labor group, and secondly to the changes in both job locations and in inhabitants’ residences. To maintain job accessibility to poorest inhabitants over time, beyond improving transport network, trying to maintain -or to move in a planned way- the location of their jobs and residence appears as a key variable.